Every motorcyclist over the age of 25 seems to have a story about a Triumph they have ridden or owned. I am no exception. Being the victim of a motorcycle which is such a common sight on British roads is something which can inspire great love for the marque or absolute hatred of all things Triumph. I myself subscribe to the former view, even though my T90 has on occasions put me through sheer bloody hell.

It all started with the discovery of a long forgotten dust sheet at the back of the garage, which upon examination concealed the partially dismantled remains of what is probably Triumph's most unremarkable machine - the sports version of the sluggish and unreliable 3TA. Namely, the Tiger 90.

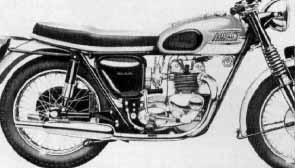

This vertical twin is similar in design to the Daytona and Bonnie, being unit construction with a four speed box, pushrod operated valves, a twin bearing crank and chain primary drive. Quality of construction is dubious but power output so low that parts last quite well and the vibes are not as mind numbing as the bigger twins. Because it's so slow, the 500s and 650s are much more common. It's only really good point being economy, as much as 75mpg possible.

After brushing away the accumulated dust and wheeling the machine out into the sunlight, all was revealed. Considering the amount of time it had been standing, the condition wasn't too bad. The paint was a mess, of course, and the wheel rims were pitted with rust, but it was at least more or less complete.

On further examination I discovered what was really missing and for the first time considered consigning it back to its dust sheet. Things like valves, guides, points, switchgear, etc don't seem like much but when you are skint it represents a hell of a bite out of the dole check.

However, after grubbing about in various boxes and tins I managed to come up with the goods except for the valves and guides which I had to pay for. The ones I had were completely shot and I had dim recollections that they were the reason it had been taken off the road in the first place.

I decided at the outset that all I required was a running machine to get me from A to B pand not a concours winner. So, I did not mind using non standard parts. These included Norton switchgear, Jap bars, etc. The respray was perhaps the most expensive part of the venture, followed by purchase of the necessary valves and guides. Parts availability seemed quite good, costing less than those for Jap bikes but not exactly at give-away prices.

When I finally decided that I had done enough it didn't look too bad considering it was a bitsa. After about an hour of kicking, bumping and swearing, the thing managed to start. Clouds of oily black smoke accompanied this but the engine sounded superb. Little did I know....Anyway, out came the old puddin' basin and Belstaff and I was ready for the off. Into first, a handful of throttle and it was away. It pulled like a train through all the gears and for about the first ten minutes all seemed well.

That is, until I noticed a strong smell of burning oil and fearing the worst I headed for home. The appalling contact breaker arrangement with the pair of capacitors inside the points cover had decided to roam around the casing at will, throwing the timing out in a big way, causing the motor to heat up like a jet engine. The oil had turned into a black soup like substance and the newly polished exhaust downpipes were a deep midnight blue.

Very nice, but after four miles? Needless to say, the points were thrown away and a marginally better set up from a Commando were substituted with the capacitors mounted more sensibly under the fuel tank. After an oil change and a bit more tinkering, it began to get quite reliable, usually starting first or second kick.

Considering the age of the suspension, handling was not too bad although bumpy roads were a literal pain in the backside because few bumps were absorbed. It would thump through town with the best of the pack, although it lacked the low down urge of the bigger twins and needed at least 3500rpm up to make it move.

On short journeys the overheating problem didn't show itself again, but long journeys could be hectic as no matter what I did concerning the timing of the beast, it still did its best to burst into flames at any and every opportunity. I was unwilling to put up with this, however, so before every journey the points cover had to come off to allow me to retime the motor.

This evil little machine eventually began to settle down, if only to lull me into a false sense of security and then the little niggling faults began to appear. Bits dropping off, disappearing rocker covers, blowing bulbs..... the kind of things Triumph owners come to expect. The rocker covers can be wired into position, headlamps insulated with additional rubber mounts and a daily check of the bolts most likely to come undone is a neat bit of preventive maintenance.

The first time the clutch cable decided to give up the ghost was mildly amusing, even though the bitch dumped me in the road to the general amusement of a pack of gas board fitters, who watched me struggle to my feet and laughed until they could no longer stand. The clutch action was heavy, as was the gearchange, although false neutrals were not common.

But the amusement really started when I had to ride the bike in the rain. This chore was usually accompanied by a constant stream of electrical faults, ending in an unannounced pyrotechnical display from the Lucas switches. This was bad enough, but when the loom actually burst into the flames the wiring harness was ceremoniously ripped off and thrown away.

After its second rewire all seemed well. But the old faults began to slowly appear, starting with the chronic problem of overheating and closely followed by electrical faults. A sane person would have thrown the lot on to the back of a scrap wagon, but once the Triumph bug has bitten it is very difficult to shake off the disease.

I decided on a full rebuild and one weekend I completed a full strip down. I wish I hadn't. The catalogue of disasters included shot wheel bearings, knackered swinging arm bushes, dodgy steering head bearings, solid rear shocks, rubber rear chain and, of course, useless electrics.

My only surprise was that the bike had managed to run at all - just shows these old bikes will still keep running even when they are in a terrible state. As I said earlier, I wasn't exactly rolling in money so most of the repairs were carried out in the traditional manner - gobs of spit, baling wire, etc.

After the rebuild and another respray, the bike didn't look half bad. I had removed the chrome plate from the items made of brass (filler cap, headlamp rim, etc) and polished them to a high lustre. The old banger looked quite beautiful but, unfortunately, still went like a pig. Much fiddling with the timing brought back some of the reliability and slowly she started to behave in a relatively normal fashion.

The clutch cable went west again and I was constantly adjusting the clutch. On one glorious day I actually saw 90mph on the clock. This was another cunningly contrived plot to deceive me into believing everything was in good order. But, of course, this was not the case.

Whilst stopped at a set of lights I happened to glance down and to my horror the crankcase was swimming in oil. The plastic rocker feed oil pipe had had enough of being heated to temperatures of that approaching the sun and had melted, spraying half the oil tank contents all over the engine. As if this wasn't enough, as I struggled home the wiring decided to join in the fun and proceeded to melt, boiling the battery in the process...

It has now been 12 months since these episodes and she is still sitting in the garage awaiting the cash for a proper rebuild, and still, after all these problems, I would recommend a Triumph to anyone. I must have lost my marbles somewhere along the way, but I guess I just love Triumphs...

Andy

****************************************************

A certain amount of new thinking is needed when dealing with old British bikes. After a decade of ever faster and flasher Japanese fours I'd bought the old Triumph on a whim. It was sitting outside the local motorcycle show with a for sale sign on it. I'd assumed it was a Bonnie or something equally fearsome. The OHV vertical twin silhouette was similar throughout the range, easily confusing innocents like myself.

Whilst I was taking in the rather faded chassis, obligatory oil leak and 76000 miles on the clock, the owner turned up. Portly, bald and Barbour clad he looked like a typical British biker. He wanted £600, kicked the T90 into life and let me have a run around the car park. It took all my concentration not to mix up the gear and brake levers, but the overwhelming impression I had was of niceness!

He accepted £500 for the 1968 model, the final year they were made. He threw in a handbook and some old road tests. The 349cc engine gave 27 horses a 7500rpm. With a bore and stroke of 58x65mm, it was no match for the usual high revving, short stroke Japanese engines but also lacked the urgent urge at low revs that most people associate with big British twins. It seemed smooth, though, better than a Superdream 400 I once had the joy of thrashing, despite a lack of balance chains and pistons that moved up and down together.

The Triumph totally lacked any primary balance, but the engine was well matched to the frame, which seemed to absorb almost all of the buzzing which emerged from the motor and was immediately apparent if I put a boot on to the engine. The chassis was shared with the bigger twins, well able to withstand the 95mph top speed. The best rev range for the engine, taking into account power and smoothness, was 5000 to 7000rpm.

Once I'd become used to using my right foot for changing gears, the box seemed very precise, especially compared with ten year old Japanese bikes, but the gaps between the four ratios were rather large, as if the box had been designed for the 650 model and bunged into the 350's unit construction casing as an afterthought. It was dead easy to stray out of the meagre power band, ending up with the kind of bland power delivery that would not impress an owner of a CG125!

I often ended up revving to 8500rpm when I needed to cover distances rapidly, just to get the speedo up to 75mph in third before changing up to top. This did cause the engine to send out a flurry of vibration, more in the pegs than the bars, but I never held those revs for long, just used them to get the speedo up to 80mph in top. One advantage of its longer stroke seemed to be that once attained, reasonable cruising speeds could be held against hills and the like without any madness on the gearbox, whereas Japanese twins would need an excessive amount of footwork.

The engine was fed by a single Amal carb that lacked a choke mechanism but had a button that could be pressed to flood the carb with petrol. I got some funny looks when I told my mates it would only start from cold if the carb was tickled. Such anti-green practices would probably have Eurocrats running around in circles like headless chickens but it seemed to me to be a very friendly way of starting the day. At least I couldn't spend hours trying to start the Triumph with the fuel turned off. The ignition switch had been bypassed, so all that was left was a hefty kick on the lever. Hot, it was a one kick affair; cold, three or four kicks. I improved on that by fitting a new set of NGK plugs in place of the Champions.

One advantage of the single carb was fuel economy, better than 70mpg! With a 3.5 gallon petrol tank that meant I could ride for over 200 miles before searching for fuel. One thing the Triumph didn't like was leaving the fuel tap on when the engine wasn't running. It'd spill out of the carb bowl unless turned off the moment the engine was stopped (usually by stalling it in first gear, there being no working kill switch).

The bike seemed well sorted by the past owner, with wired in bolts, steel oil lines and a decent set of Avon tyres. It had the feel of a well tended cycle. After a faultless initial 1000 miles it seemed like a good idea to check the valves and points. The Triumph has pushrod valves with rockers in the head and camshafts atop the crankcases. I was quite impressed to find the cams driven by gears. The exhaust valve clearances were way out but with their screw and locknut adjusters were easy to set up. The points were spot on. The pushrod tubes leaked oil, but they all seem to do that.

Oil went through the engine at 100mpp, with a five pint oil tank under the seat it meant carrying an extra supply of oil if I wanted to do more than 300 miles in a day. A quick way to check the oil pump is to see if the oil's coming back to the tank, although sometimes there's a bit of pressure build up and taking the cap off results in an eyeful of oil. Once, I'd found the tank almost empty after leaving the bike overnight. Filled it up only to have oil spewing out everywhere; a couple of pints had lodged in the crankcases, when it started circulating again there was too much oil for the system to contain.

The Triumph is full of such traps for the unwary. The front brake was another item of contention. A quite large SLS unit, I thought it was rather nice, with extremely controllable power. Lovely in the wet, but a couple of hard stops would turn it to mush. I was used to crap Japanese discs that would seize up the first time winter fell, but at least they were predictable. The SLS drum would work well sometimes, other times the lever would pull all the way back to the bars. A common mod is to fit the TLS front wheel from the Bonnie, so I tracked one of these down, a bit shocked to have to hand over £75 for a nice one. It was a fantastic improvement but not so nice in the wet.

The forks and shocks were stiff, short travel items that gave the Tiger 90 a nice taut feel after the vague, loose Japs of my immediate past. The going over that my spine took, despite a well designed seat and reasonable riding position, was worse than on the Japs. Given the way it could be banked over and didn't wander even on bumpy roads it was a small price to pay.

The Triumph weighed in at 335lbs, lighter than most Japanese 250 twins to which its performance could be equated. A lot of this mass was down to the lack of luxuries. Not even indicators were fitted, the 60 watt alternator allowing only the most basic of lights and coil ignition circuit. It took me a while to track down the rectifier and regulator, it was a home-made job on a big alloy heatsink. The electrical components were encased in plastic and the alloy mounted on rubber. The small 12V battery would've looked at home in a modern 125. Despite all that the system functioned without problems, deep rubber HT caps making sure there was no cutting out in the wet.

The front light was good only for 30mph on unlit roads and even in town I found myself revving the motor to make sure cagers knew I was there. Bulbs blew a couple of times but I always made it home, using the stoplight or pilot beam.

The first engine problem was a sudden clattering noise from within the primary chaincase. The crankshaft is connected to the clutch by a duplex chain, a leftover from the days when engine and gearbox were separate units. There is a belt conversion but it's far too expensive. I put in a new chain and a new set of clutch plates, as the old ones were a bit warped. Clutch drag was becoming a real nuisance in town.

That was about 3500 miles after I'd bought the bike. It ran for the next 6000 miles, gradually losing some power and increasing the amount of smoke out of the exhaust. It was a combination of worn bores and valvegear. Unfortunately, the bores were already on their largest overbore and there were cracks in the combustion chamber. I was tempted to try to fit a 500cc top end, as the bottom half of the motor is supposed to be similar. 350 bits are much less common than for the bigger engines but just as I was about to buy the 500cc parts I found a private seller with a couple of boxes of 350 Triumph parts.

Rebuilding the motor I was continually surprised at how easily it all went together. The only difficult part was making sure the pushrods stayed properly located. I was careful torquing down the head, not wanting the casting to crack. Too little pressure resulted in a blowing gasket, too much in a ruined head. You have to have a little mechanical sympathy.

The rebuilt motor was run in for 750 miles then given its head. Very briefly I put the ton on the clock. Too much vibration to hold for more than a few moments, but the motor was stronger tuned than originally and I was suitably impressed with my ability as a mechanic, although most of it was down to the simplicity of the engine.

Whilst the motor was out I'd hand painted the frame and resprayed the tank and panels. Everything in gloss black. It still doesn't look like new, though, it'd need rebuilt wheels, new exhaust and a few other minor bits - they'll have to wait until I have some more free cash.

The Triumph 350 is one of those bikes you spend all your free cash on, enjoy the more you ride it and can take a real pride in. A little bit of caution is needed when buying one, though, there are lots of rats around.

I.K.G.

****************************************************

A certain amount of new thinking is needed when dealing with old British bikes. After a decade of ever faster and flasher Japanese fours I'd bought the old Triumph on a whim. It was sitting outside the local motorcycle show with a for sale sign on it. I'd assumed it was a Bonnie or something equally fearsome. The OHV vertical twin silhouette was similar throughout the range, easily confusing innocents like myself.

Whilst I was taking in the rather faded chassis, obligatory oil leak and 76000 miles on the clock, the owner turned up. Portly, bald and Barbour clad he looked like a typical British biker. He wanted £600, kicked the T90 into life and let me have a run around the car park. It took all my concentration not to mix up the gear and brake levers, but the overwhelming impression I had was of niceness!

He accepted £500 for the 1968 model, the final year they were made. He threw in a handbook and some old road tests. The 349cc engine gave 27 horses a 7500rpm. With a bore and stroke of 58x65mm, it was no match for the usual high revving, short stroke Japanese engines but also lacked the urgent urge at low revs that most people associate with big British twins. It seemed smooth, though, better than a Superdream 400 I once had the joy of thrashing, despite a lack of balance chains and pistons that moved up and down together.

The Triumph totally lacked any primary balance, but the engine was well matched to the frame, which seemed to absorb almost all of the buzzing which emerged from the motor and was immediately apparent if I put a boot on to the engine. The chassis was shared with the bigger twins, well able to withstand the 95mph top speed. The best rev range for the engine, taking into account power and smoothness, was 5000 to 7000rpm.

Once I'd become used to using my right foot for changing gears, the box seemed very precise, especially compared with ten year old Japanese bikes, but the gaps between the four ratios were rather large, as if the box had been designed for the 650 model and bunged into the 350's unit construction casing as an afterthought. It was dead easy to stray out of the meagre power band, ending up with the kind of bland power delivery that would not impress an owner of a CG125!

I often ended up revving to 8500rpm when I needed to cover distances rapidly, just to get the speedo up to 75mph in third before changing up to top. This did cause the engine to send out a flurry of vibration, more in the pegs than the bars, but I never held those revs for long, just used them to get the speedo up to 80mph in top. One advantage of its longer stroke seemed to be that once attained, reasonable cruising speeds could be held against hills and the like without any madness on the gearbox, whereas Japanese twins would need an excessive amount of footwork.

The engine was fed by a single Amal carb that lacked a choke mechanism but had a button that could be pressed to flood the carb with petrol. I got some funny looks when I told my mates it would only start from cold if the carb was tickled. Such anti-green practices would probably have Eurocrats running around in circles like headless chickens but it seemed to me to be a very friendly way of starting the day. At least I couldn't spend hours trying to start the Triumph with the fuel turned off. The ignition switch had been bypassed, so all that was left was a hefty kick on the lever. Hot, it was a one kick affair; cold, three or four kicks. I improved on that by fitting a new set of NGK plugs in place of the Champions.

One advantage of the single carb was fuel economy, better than 70mpg! With a 3.5 gallon petrol tank that meant I could ride for over 200 miles before searching for fuel. One thing the Triumph didn't like was leaving the fuel tap on when the engine wasn't running. It'd spill out of the carb bowl unless turned off the moment the engine was stopped (usually by stalling it in first gear, there being no working kill switch).

The bike seemed well sorted by the past owner, with wired in bolts, steel oil lines and a decent set of Avon tyres. It had the feel of a well tended cycle. After a faultless initial 1000 miles it seemed like a good idea to check the valves and points. The Triumph has pushrod valves with rockers in the head and camshafts atop the crankcases. I was quite impressed to find the cams driven by gears. The exhaust valve clearances were way out but with their screw and locknut adjusters were easy to set up. The points were spot on. The pushrod tubes leaked oil, but they all seem to do that.

Oil went through the engine at 100mpp, with a five pint oil tank under the seat it meant carrying an extra supply of oil if I wanted to do more than 300 miles in a day. A quick way to check the oil pump is to see if the oil's coming back to the tank, although sometimes there's a bit of pressure build up and taking the cap off results in an eyeful of oil. Once, I'd found the tank almost empty after leaving the bike overnight. Filled it up only to have oil spewing out everywhere; a couple of pints had lodged in the crankcases, when it started circulating again there was too much oil for the system to contain.

The Triumph is full of such traps for the unwary. The front brake was another item of contention. A quite large SLS unit, I thought it was rather nice, with extremely controllable power. Lovely in the wet, but a couple of hard stops would turn it to mush. I was used to crap Japanese discs that would seize up the first time winter fell, but at least they were predictable. The SLS drum would work well sometimes, other times the lever would pull all the way back to the bars. A common mod is to fit the TLS front wheel from the Bonnie, so I tracked one of these down, a bit shocked to have to hand over £75 for a nice one. It was a fantastic improvement but not so nice in the wet.

The forks and shocks were stiff, short travel items that gave the Tiger 90 a nice taut feel after the vague, loose Japs of my immediate past. The going over that my spine took, despite a well designed seat and reasonable riding position, was worse than on the Japs. Given the way it could be banked over and didn't wander even on bumpy roads it was a small price to pay.

The Triumph weighed in at 335lbs, lighter than most Japanese 250 twins to which its performance could be equated. A lot of this mass was down to the lack of luxuries. Not even indicators were fitted, the 60 watt alternator allowing only the most basic of lights and coil ignition circuit. It took me a while to track down the rectifier and regulator, it was a home-made job on a big alloy heatsink. The electrical components were encased in plastic and the alloy mounted on rubber. The small 12V battery would've looked at home in a modern 125. Despite all that the system functioned without problems, deep rubber HT caps making sure there was no cutting out in the wet.

The front light was good only for 30mph on unlit roads and even in town I found myself revving the motor to make sure cagers knew I was there. Bulbs blew a couple of times but I always made it home, using the stoplight or pilot beam.

The first engine problem was a sudden clattering noise from within the primary chaincase. The crankshaft is connected to the clutch by a duplex chain, a leftover from the days when engine and gearbox were separate units. There is a belt conversion but it's far too expensive. I put in a new chain and a new set of clutch plates, as the old ones were a bit warped. Clutch drag was becoming a real nuisance in town.

That was about 3500 miles after I'd bought the bike. It ran for the next 6000 miles, gradually losing some power and increasing the amount of smoke out of the exhaust. It was a combination of worn bores and valvegear. Unfortunately, the bores were already on their largest overbore and there were cracks in the combustion chamber. I was tempted to try to fit a 500cc top end, as the bottom half of the motor is supposed to be similar. 350 bits are much less common than for the bigger engines but just as I was about to buy the 500cc parts I found a private seller with a couple of boxes of 350 Triumph parts.

Rebuilding the motor I was continually surprised at how easily it all went together. The only difficult part was making sure the pushrods stayed properly located. I was careful torquing down the head, not wanting the casting to crack. Too little pressure resulted in a blowing gasket, too much in a ruined head. You have to have a little mechanical sympathy.

The rebuilt motor was run in for 750 miles then given its head. Very briefly I put the ton on the clock. Too much vibration to hold for more than a few moments, but the motor was stronger tuned than originally and I was suitably impressed with my ability as a mechanic, although most of it was down to the simplicity of the engine.

Whilst the motor was out I'd hand painted the frame and resprayed the tank and panels. Everything in gloss black. It still doesn't look like new, though, it'd need rebuilt wheels, new exhaust and a few other minor bits - they'll have to wait until I have some more free cash.

The Triumph 350 is one of those bikes you spend all your free cash on, enjoy the more you ride it and can take a real pride in. A little bit of caution is needed when buying one, though, there are lots of rats around.

I.K.G.