Sunday, 2 September 2018

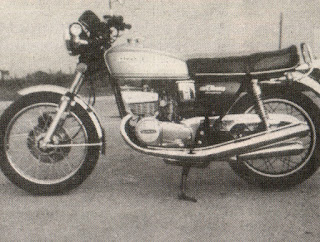

Suzuki GT380

Why buy an eight year old two stroke with appalling handling and miserable fuel economy? My excuse was as a cheap hack while my XS850 was being repaired, though to be honest nostalgia was probably the main reason. When I was an impressionable teenager, a friend with a shiny red GT380 had startled me with its brute power, achieving the heady speed of 89mph two up, down the local dual carriageway.

Seeing the forlorn S-reg GT380 going for only 250 quid in a dealers, l blinded myself to the rust, the leaky forks and the questionable tyres. I even believed the salesman’s promise that the bike would be serviced before I collected it. When I turned up, it wouldn't even start until new plugs had been fitted and a battery borrowed from a hapless Kwacker. I should have guessed what was in store for me when asked to sign a disclaimer form, stating that the bike was unfit to ride and being sold for repair only; but love is blind.

I arrived home with only momentary panic when I thought the locking fuel cap was going to stay jammed, leaving me with only a tablespoonful of petrol left in the tank. I noticed that the brake light didn’t seem to work, then realised that with bikes of this age it was triggered only by the rear brake - hardly useful, when most of the braking is done with the front!

The indicators didn't, even after charging the battery. Neither did the dip position on the headlight. A new flasher unit and headlamp bulb cured these faults. I also needed some ingenuity to fix one of the side panels, on which mounting lugs had broken, and to add a chainguard (missing when bought).

For the uninitiated, the GT380 has a three cylinder in-line two stroke engine, with six gears and a handy digital gear display. Oil is stored in a separate oil tank (beneath the seat) and delivered to main bearings and carb inlet by the trusty CCI system. The engine also features the Ram Air system which supposedly directs air through the cooling fins to cool the engine. How this differs from other air cooled engines I was never sure - my machine was missing the top cowling but seemed none the worse for that.

After my first trip of twenty miles, the bike became rough at tickover, then stalled a few times and finally refused to start. A quick check revealed plenty of petrol, but no spark. The battery was flat. At 377lbs, the bike was no heavyweight but I thought I’d bought a GS1000 by mistake after pushing it two and a half miles. I bought a new battery - despite this, the bike didn’t run well but got me home.

I began to investigate the charging circuit, recalling the rumours I'd heard about Suzuki electrics. I found that the OEM rectifier had been replaced by two bridge units but the bodge seemed to work. The regulator, a simple mechanical type, performed better once its contacts had been cleaned up. Where, then, were the missing volts? The alternator, it turned out, had had one set of coils sawn through in a vain attempt to sort out a short.

Finding a replacement alternator was not easy. I ordered one from a breakers which didn't arrive. I went in search of a firm said to rewind alternators but no-one had heard of them at the given address. For a while, I rode on a total loss basis which meant charging the battery both at home and at work during the winter. In the end, I rewound the alternator myself - a fiddly and disheartening job.

Back on the road again, I found that under sharp braking the rear wheel locked up and threatened to chuck me down the road. I bought some new brake shoes and pads in the hope of improving matters. At the front was a single disc, and neither the new pads nor a thorough bleeding of the hydraulics improved its efficiency. It always felt spongy. I suppose with hindsight some Goodridge would have helped.

The forks had little damping and oil appeared to be leaking. Removing the dust covers, I discovered a cunning dodge someone had packed out the space with kitchen tissue, which would absorb leaking oil long enough to sell the bike. I fitted new fork oil seals. With the 235cc of oil advised by the manual, the forks locked up painfully on meeting London potholes, doing untold damage to the new seals. I removed a few cc and the handling improved. Replacing the rear shocks (which looked like the originals) might have helped further, but would have defeated the point of a cheap second bike.

When I bought the bike, there was a sticker over the speedo disclaiming the measured mileage, but as it read 37000 miles I didn't think it had been clocked, anyone taking the trouble would have set it a bit lower - 27000 miles perhaps. I'd originally bought the bike with thoughts of restoring it, but just keeping it on the road was hard enough. Somehow, I got an MOT, though the tester reckoned the forks were twisted and the headstock loose. The instrument glasses were horribly scratched but rubbing in engine oil made them more transparent.

I never found out what the top speed of the machine was. as I didn’t take it on a long enough road. Its acceleration wasn't bad, though, provided it was thrashed mercilessly. At the traffic light GP, it usually kept up with bigger four strokes. After a larger bike, I found that I had to ride more smoothly, keeping the momentum up and relying less on hard acceleration or frantic braking to make rapid progress. To that extent, I guess riding the bike improved my riding style. The downside was the unpredictable handling, soft suspension, abysmal tyres and poor brakes.

The styling and overall design of the cycle parts were dated. The alloy crankcases had that classic Jap crap look; the spoked wheels with pseudo chromed rims were hard to keep (read get) clean. The three into four exhaust collected muck and added pounds to the overall weight. It also rattled annoyingly near where it joined the barrels, but tightening up the exhaust studs did nothing to cure it.

Overall, what were the good points? The engine design was simple - no reed or rotary valves. It had a basic ignition system, with no expensive electronics. The oily exhaust of a two stroke meant that the bike still had the original silencers after eight years.

Servicing was easily performed without the benefit of an engineering degree or portable computer. I wouldn’t go as far as the Haynes manual - searing acceleration, quiet running and almost complete absence of vibration, but then I didn't have one from new. Neither did I keep the bike long enough to need to change the tyres, but judging from the apparent age of the ones fitted, they would have rotted before they wore out.

Bad points? Handling, as above. Fuel economy was only acceptable (40mpg) if you didn't use the performance. It was heavy (a GPz500 is 2lbs lighter; an FT500 25lbs). It has three sets of points to adjust and three carbs to set - for 37hp?

To put the bike into perspective, it had the performance of, say, a Suzuki 250 X7 or a well thrashed RD250LC. Handling was as good as one could expect considering the age of the machine. Sure, it would be possible to improve matters - religiously renew the steering head bearings, swinging arm bearings, get the rims re-spoked, upgrade the suspension, etc. - but at what cost?

And, you'd still only end up with a machine as good as the basic frame design would allow. No, a bike like this only makes sense if bought for peanuts and run into the ground. My definition of a cheap hack is a bike which costs next to nothing to run, starts reliably and isn’t in imminent danger of being stolen. The GT380 met only the last of these conditions, and the alternator fault had returned, so I put it up for sale. A lad offered me £55, which seemed fair enough. I even threw in the box of spare parts I'd accumulated for it. In fact, I was so sick of the heap I'd have given it away!

B P Munt